Russia Up Close

A Finnish adolescence by the Soviet border - and the deeper roots of Moscow’s strategic mindset

As I mentioned in my announcement yesterday, this renewed newsletter will cover four themes; Geopolitics, Innovation & Deeptech Policy, Funding and Financing, and Culture & Ideas.

On Geopolitics, I said “being a Finnish GenX woman who grew up right next door to the Soviet Union, I will increasingly focus on Russia’s influence on the West”. In this first post about Russia, I will go to the backend, the Russian mindset.

Growing up, the Soviet Union was Finland’s largest trading partner. Although Finland was militarily neutral, it never belonged to the Warsaw Pact and was considered west of the iron curtain, it’s politics were heavily influenced by the Kremlin. This period, and the seemingly voluntary, but in “realpolitik” involuntary behavior has been called Finlandization.

I spent a year in New Jersey between Junior High and High School. Before I left, I had to make the selection of languages I would take in high school when I return to Finland. My best friend wanted to become a businesswoman, so she chose Russian. I already studied Swedish, English, and French, so I agreed to join the Russian classes with her just for fun. A year later when I returned from the U.S. I was no longer interested in taking Russian (I mean, this is the 1980’s and I had just spent a year watching MTV - hello!), but it was too late so I spent three years in high school studying the Russian culture and language, making class trips to Leningrad, and welcoming Russian visitors in our home town.

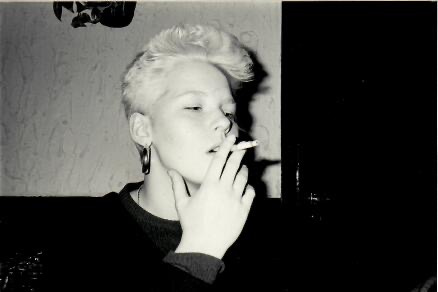

Here I am, 1986, back from the US and cool as fork as you can see lol ;)

A few years later, just before the USSR collapsed, I helped out with my very basic Russian to translate for an underground network smuggling “refuseniks”, Soviet Jews who were denied permission to emigrate to Israel legally. But that’s another story.

I’m definitely no Russia expert, but I have a fairly good understanding of the culture and the mindset.

Russia's Strategic Culture

One of the nice thing of speaking Finnish (or Estonian, or other Baltic languages) is that you have a wealth of Russia expertise at your fingertips. I’ve read many good books on geopolitics, but this one video from 2018 has stuck with me. It’s a one hour university lecture by a former Finnish Intelligence Colonel Martti J. Kari (1960-2023), and titled “Russian strategic culture - Why Russia does things the way it does?” The Finnish video has English subtitles, and there’s also a bad AI english voiceover here.

Let’s break down the key themes and messages from Col. Kari’s lecture.

The Soul of the Bear: Unpacking Russia's Strategic Culture

To understand Russia's actions on the global stage, we have to look beyond a simple list of political decisions and military movements. We need to delve into something much deeper: its strategic culture. This is the collection of historical, geographical, and cultural beliefs that shape how Russia perceives the world, its place in it, and the threats it faces. It’s a lens through which Moscow sees everything, from its relationship with its neighbors to its role as a global power. By tracing the roots of this unique worldview, we can begin to see that its choices, which often appear irrational to the outside world, are in fact a logical continuation of centuries of deeply ingrained lessons.

The Deepest Roots: Byzantium, Mongols, and the "Third Rome"

The foundation of Russian strategic culture lies in its ancient past, beginning with its Slavic cultural roots. This shared heritage of language and identity created a fundamental sense of unity among the Slavic peoples, a feeling that persists to this day, which I well sensed during my work with the Republic of Serbia between 2022-2024.

This sense of shared identity was profoundly shaped by the adoption of Orthodox Christianity and the influence of the Byzantine Empire. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow came to see itself as the new center of the Orthodox Christian world, the "Third Rome." This belief imbued authority with a sacred quality, establishing the idea that power comes from God and should not be challenged. This religious and political doctrine created a society where autocracy wasn't just a political system, it was a divine mandate.

However, this early formation was brutally interrupted by the Mongol influence, which had already began in 1240. The Mongol rule was a period of extreme cruelty, corruption, and harsh taxation. The very structure of Mongol power, where a single Khan ruled with absolute authority and others were mere subjects, left a lasting imprint on Russian political thought. Survival during this era depended on a ruthless obedience to a strong, centralized leader.

The Mongols eventually assimilated into Russian society, but their cultural and genetic legacy left an enduring lesson: authoritarian leadership is the only way to maintain order and survive. The “Time of Troubles” in the early 1600s, when Poland briefly controlled Moscow, further cemented this lesson. With no clear ruler, the country descended into chaos, reinforcing the belief that a strong leader, no matter how harsh, is always better than civil disorder. Only an autocracy, it seemed, could truly save Russia from itself.

The Tug of War: East vs. West

From the early 1700s onward, Russia has been locked in a perpetual debate with itself: is it European or is it a unique Eurasian power, part of the East? This struggle for identity continues today. While Russia rose as a great power in Europe, it also consciously created a sense of mystery around itself through its literature and theater. You could think of the great Russian authors and poets as sort of the first wave of information warfare. This duality is central to its worldview, allowing it to be both a great European power and a unique civilization unto itself, unburdened by Western liberal norms.

This great power tradition was inherited by the Soviet Union and continues to drive Russia's modern foreign policy. The concept of geopolitical spheres of influence is not just a policy, it’s a fundamental historical belief that Russia is “entitled” to a buffer zone of friendly states on its periphery. The lessons of World War II, a war that cost 27 million Soviet lives, solidified this belief, reinforcing the idea that it's better to fight an enemy abroad than to allow a conflict to spill into its own borders.

Col. Kari gave this lecture in 2018, four years after Russia had claimed Crimea, and four years before the full blown invasion of Ukraine. How right he was.

Geography and the Militaristic Mindset

Perhaps the most potent driver of Russian strategic culture is its vast geography. Spanning 11 time zones with immense, open plains, Russia has been historically vulnerable to invasion.

From the horsemen of the Mongols to Napoleon’s and Hitler's tanks, the country has been repeatedly invaded from the West. This historical reality has created a deep-seated national insecurity and the belief that invasion is an ever-present and inevitable threat. The only reliable defense against this vulnerability is a strong, centralized leader and a formidable military. This is why militarism is such a core part of the Russian identity, manifesting in a long tradition of fighting “small wars on the periphery” to maintain national spirit and assert its dominance. As long as bombs don’t hit Moscow it’s gonna be alright.

American diplomat George Kennan, a keen observer of the Soviet Union, famously articulated this mindset in 1946: “The Kremlin’s neurotic view of world affairs is based on their traditional and instinctive insecurity.” He also noted that

“Russia is Deaf to the Logic of Reason but very Sensitive to the Logic of Power.”

This is a mindset that prioritizes strength and military might above all else, seeing it as the only language a truly dangerous world understands. As Lenin once said, an expression I heard many times growing up, you must “probe with a bayonet. If it’s soft, push; if it’s hard, withdraw.” This quote captures the essence of a strategic culture that tests boundaries and only backs down when it meets overwhelming force. I don’t know why I’m so familiar with this quote, if someone was trying to educate me how to behave in the playground, then.. oh my.

The Two Realities and Information Warfare

A key aspect of the Russian national character is its unique relationship with truth and information. This culture is marked by a dual existence: the private “kitchen-table reality,” where people speak freely and honestly among friends and family, and the public, official reality, where they repeat what is expected and safe. This duality, a legacy of the Soviet era and the homo sovieticus mindset, has created a society that is accustomed to living with conflicting truths.

I literally experienced the kitchen table reality once in Leningrad, where I was invited to an apartment of a new friend I just made. She told me to switch jackets with her and be quiet as we entered the apartment building. Only once we were safe in the kitchen where her mother offered us tea with thick jam, were we free to talk. Her mother was not happy to have me there, but she was very polite. I would never know if they got into any trouble for having a Westerner in their home. (by the way, this was the first time I ever tasted a persimmon, there were some exotic fruits that the Soviets had from their orchards by the Black Sea that we did not get in Finland).

This is the foundation for Russia’s modern “information geopolitics,” a sophisticated blend of crude and subtle propaganda. The crude messaging (like outlandish conspiracy theories) serves to distract and sow chaos, while the more sophisticated propaganda (like carefully crafted historical narratives) works in the background, shaping perceptions over time. This approach, which the phrase “useful idiots” still perfectly describes, is designed to confuse and paralyze adversaries, making it difficult to discern truth from fiction. This is not a new tactic, but a modern evolution of a tradition of truth and lies that stretches back to the Mongol era.

A History-Driven Worldview

Russia’s strategic culture is intensely history-driven, particularly in its views on its neighbors. As mentioned, the country’s poets and historians have shaped its perspective on others for centuries.

For example, Russian views on the Finns are colored by Pushkin’s poem The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale. It is a narrative poem written by Alexander Pushkin in 1833 about the equestrian statue of Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg and the great flood of 1824. Wikipedia says the Bronze Horseman is widely considered to be Pushkin's most successful narrative poem, and has had a lasting impact on Russian literature. The Pushkin critic A. D. P. Briggs praises the poem "as the best in the Russian language, and even the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century". Again from wikipedia; “it is considered one of the most influential works in Russian literature and is one of the reasons Pushkin is often called the founder of modern Russian literature".

This cornerstone of Russian literature, perhaps “the best poem written anywhere in the nineteenth century” describes the Finns as “wretched” and “a miserable stepchild of nature” whose waves "bang their heads against the city's walls”, the city built “where Finnish fisherman before, Harsh Nature’s wretched waif, was plying”. This type of historical and literary framing of other peoples is not a footnote; it is a fundamental part of how Russians view themselves and their relationships with other nations, in this case with Finland.

Ultimately, Russia’s strategic culture is a complex, layered product of a long history of invasions, a sense of divine purpose, and a deep-seated geographical insecurity. It is a worldview that values a strong leader above all else, believes in the necessity of a militarized state, and sees truth as a tool to be used rather than a principle to be upheld.

As Vladimir Putin once said, “Whoever controls AI will control the world.” This quote, like so many of his others, is not a simple statement about technology; it is a reflection of a strategic culture that is always looking for the next tool to assert its power and ensure its survival in a world it views as fundamentally hostile.

Please help me develop the newsletter further by answering this poll:

From the Archives

Open - The Progressive Case for Free Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital (from January 2024)

Kimberly Clausing's book defends the global economic integration, and suggests ways for Americans to first of all, ride along and not become crushed by international realities, but also to create national policies within the U.S. to equip workers for the modern economy, better tax policies, and better partnerships between tax payers and businesses.

Conversation with a former CIA Officer

I had the honor to re-invite Laura Thomas to Deep Pockets. She is the current Chief Strategy Officer at Fuse, a fusion energy company building towards a clean and near limitless energy source. She is also a former Chief of Staff at a quantum technology company, Infleqtion, and a former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) case officer and Chief of Base.