I was listening to a recent Freakonomics podcast episode, and thought it introduced a refreshing and thought provoking way of thinking about the relationship between the U.S. and China. The episode is titled “China Is Run by Engineers. America Is Run by Lawyers”.

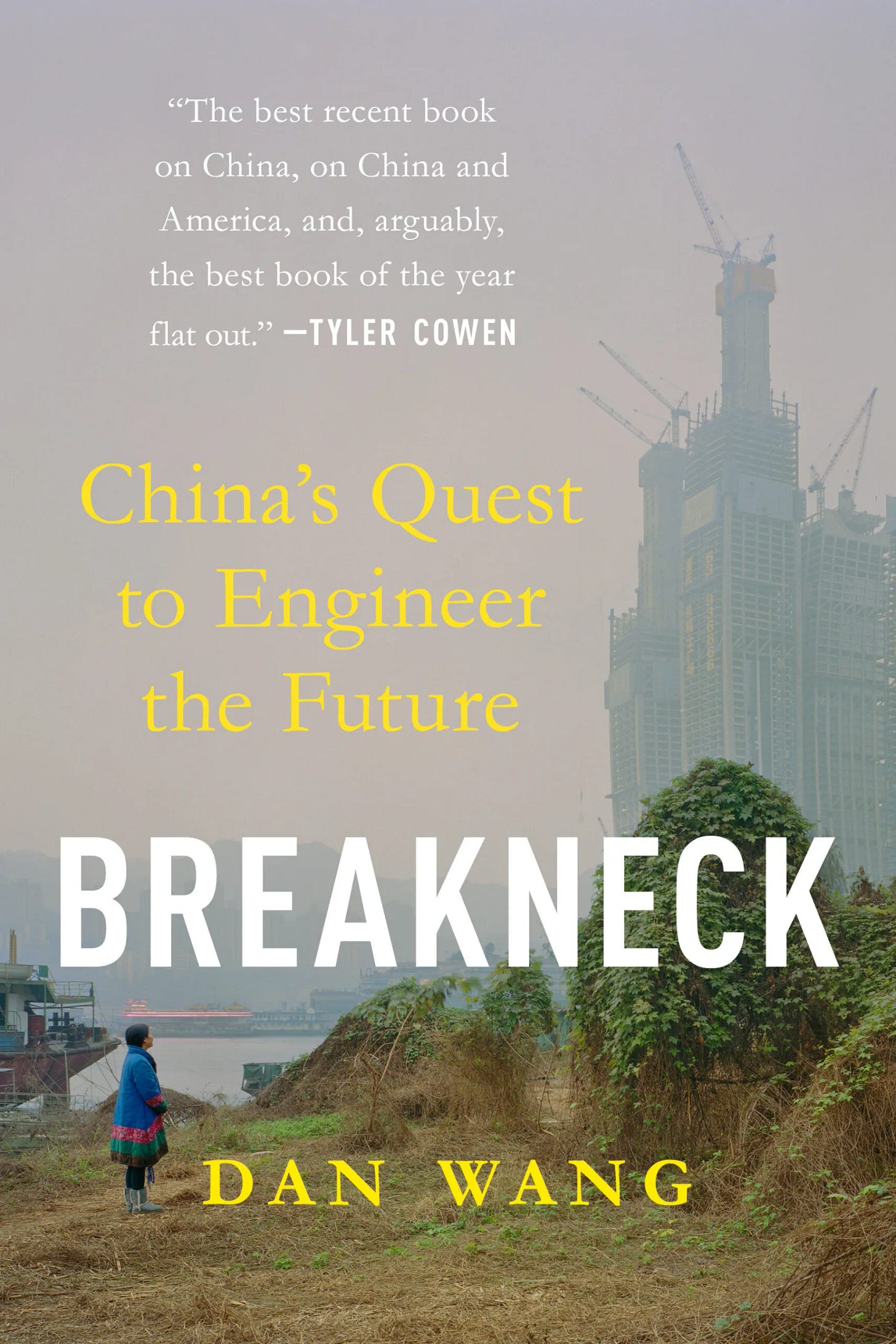

You cannot imagine how refreshing it is for me to hear a snarky one-liner about this stuff that is not punching Europe in the face (“America Innovates - Europe Regulates”, anyone?) Although, Steven Dubner, the host of Freakonomics, and his interviewee, Dan Wang, the author of Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, do end up finding common ground in their debate about the characteristics between the U.S. and China, by agreeing that Europe is a “Mausoleum Economy”. Nice one.

We're all used to hearing about the rivalry in terms of political systems - democracy versus autocracy - but what if the real difference lies in something much simpler? What if one country is run by engineers and the other by lawyers?

That’s the compelling idea from Dan Wang, a Canadian author and researcher who spent years living and working in China. In his view, China is fundamentally an engineering state, driven by a mindset focused on building and solving problems at a massive scale. The United States, by contrast, is a lawyerly society, one that is more concerned with argument, procedure, and litigation than with construction.

This simple and clever framework immediately clicked for me, so I wanted to share Dan Wang’s thoughts on how these two superpowers operate.

The "Engineer of the Soul": China's Drive to Measure and Build

As Wang explained, China's leaders often have an engineering background. This has created a culture where the solution to any problem - economic, social, or political - is to build something. This isn't just about constructing physical infrastructure like dams, high-speed railways, and megacities. It extends to social issues as well. In China’s worldview, the population and social construct is seen as a system to be engineered, optimized and controlled.

This engineering mindset has led to incredible achievements. The country has pulled hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and built impressive infrastructure at a pace that the rest of the world can barely fathom. But as the conversation made clear, there is a serious downside to this kind of thinking. When leaders see society as just another optimization problem, it can lead to troubling outcomes.

Wang describes how these policies are often named with a number, to drill down the end game and promote accountability.

For example, the one-child policy, a vast social experiment that ran between 1979-2016 that allowed for married couples to only have one child, which was designed to control the overpopulation. Or the "Zero Covid" period, which Wang himself attended as he was stranded in China for three years. He describes this experience as eye-opening. The government’s response to Covid was a perfect example of the engineering state in action: a problem was identified, and a drastic, top-down solution was applied with total force, no matter the human cost. The extreme lockdowns and the abrupt, unprepared ending of the policy revealed a system that prioritizes control above all else.

Wang’s personal accounts from all of his time in China showed a society that could be both incredibly dynamic and frighteningly fragile, a place where people learned to live with a dual reality, one public and one private (which ties well together with my piece on why Russia does the things it does).

A third policy that’s named with a number is of course well know to all of my tech policy readers, China 2025, that I wrote extensively in my book Government and Innovation.

The Lawyer's Block: A Society That Says "Hold On - No"

On the other side of the world, the U.S. operates on a completely different set of principles. Wang explained that our American society is guided by a lawyerly mindset which goes back to our founding, with many of the Founding Fathers being trained in law, and continues to this day, with a significant number of our political leaders having legal backgrounds.

For example, roughly half of U.S. presidents have been lawyers, and so have many cabinet members and top policymakers. In contrast, very few engineers rise to that level. Around a third of these lawyer presidents went to Ivy League schools, with Yale in particular overrepresented. Wang also emphasizes that the administrative class in Washington is dominated by lawyers, which shapes how problems are approached through regulation, litigation, and interpretation, rather than engineering-style problem-solving.

In the Biden administration more than half of Biden‘s senior staff of more than 50 had law degrees, even though most are in roles without a legal focus, and out of roughly 140 lawyers in the White House, approximately 36 hold degrees from Yale Law School.

Our current Vice President also has a law degree from Yale.

Why is this relevant? As they discuss in the podcast, the core function of a lawyer is to say "no" and to protect existing rights and interests. In America, this has created a system that is excellent at protecting individual freedoms and property rights, but the issue with this is, that only those who already have freedom and property are protected.

Additionally, it also means that our society is often paralyzed when it comes to building big new things. The conversation highlighted a key paradox: while we have a history of incredible engineering feats like the interstate highway system, great dams and bridges, we now struggle to even maintain our existing infrastructure. We're a society that is great at protesting and litigating but terrible at building.

The podcast gave the example of New York City's subway system, where the cost to build a single mile of track was many times higher than building an entire subway system in Europe, under the exact same natural constraints. This isn't because of a lack of talent or resources, but because the process is bogged down by lawsuits, regulations, and procedural hurdles. According to this narrative, it’s a culture where the ability to "block" is often more powerful than the desire to "build."

A New Lens on an Old Problem

What I found most compelling about this whole conversation is the curious and civil manner of peeling the onion and uncovering insight. It's not about which system is inherently "better," but about intellectual sparring, understanding the very different strengths and weaknesses, quirks and beliefs, of each.

Wang's personal journey, a man born in China, grew up in Canada, married to an Austrian, who now lives in the U.S. and looks at both the U.S. and China from the perspective of an outsider, gives him a unique vantage point. He experienced firsthand how Chinese censorship works, describing it with an old Chinese metaphor: the "anaconda and the chandelier." A story about a fancy dinner party underneath a chandelier which has an anaconda wrapped inside. The anaconda will drop on anyone at the dinner table if they say anything inappropriate. It’s not clear to the diners what is inappropriate and what’s not, so they keep the conversation in sure-to-be-safe topics. The threat is always there, but you never know when it will strike and why, leading to a pervasive culture of self-censorship.

The podcast ultimately offered a powerful takeaway. By viewing the two superpowers through this new lens, we can see why one is so good at building and one is so good at preserving. It helps explain why the U.S. struggles with infrastructure while China struggles with individual freedom. It's a sobering reminder that every system has its tradeoffs. And as these two countries continue to shape the world, understanding their core cultural operating systems is more important than ever.

About Deep Policy

Stay relevant and connect the dots.

Hi, I’m Petra Söderling. Welcome to Deep Policy, a space where I help you understand how governments, technology, and innovation policy shape the world around us.

This newsletter and blog continue the conversation I began in my book Government and Innovation – the Economic Developer’s Guide to Our Future, and on my podcast Deep Pockets with Petra Soderling. If you’ve ever wondered why governments pour billions into quantum, AI, or biotech, or how geopolitics bends the path of technology, you’re in the right place.

Every week, I share a mix of deep-dive essays, timely analysis, and cultural reflections, always with an eye toward what matters for you: the choices being made now that will shape your future economy, your industry, and your society.

Additional Resources

For more analysis, insight, maybe some entertainment, please feel free to explore these:

Petra Soderling & Co advisory services

Consulting governments, NGOs and companies on the economic and financial impact of deeptech. It’s not just me, it’s a whole team! Selected testimonials for my work from private clients can be found here. A banner with most notable public clients can be found here.

Deep Pockets Podcast

Every second week, more or less diligently, I bring forward a guest to discuss all things in the intersection of government and innovation.

The Book: Government and Innovation - the Economic Developer’s Guide to our Future

My 2022 Amazon Hot New Release (editorial pick) is divided in three sections; the Tools that governments have to create new innovative industries, Examples from five countries who’ve done it right, and a How To section for implementation. Available in paperback or hard cover.

The audiobook: Government and Innovation - the Economic Developer’s Guide to our Future

My 2022 Amazon Hot New Release (editorial pick) is divided in three sections; the Tools that governments have to create new innovative industries, Examples from five countries who’ve done it right, and a How To section for implementation. Available in paperback or hard cover.

Quantum Strategy Institute

In my role as the Head of Government and Consortium Relations at QSI, I’ve written many papers on how public quantum strategies support economic growth. Explore the full website or find my articles directly here.

This is such a critical and well-articulated distinction. This is exactly what i found out in Hefei , where the municipal government operates like a venture capital firm led by scientists. The mayor a quantum physicist doesn’t just regulate; she participates in technical reviews as a peer. Their investment team is composed of 120+ PhDs in fields from photonics to electrochemistry.

The result? They don’t just manage markets they architect them. They built a "trinity" model that functions like an algorithm: taking equity stakes in strategic companies, clustering supply chains, and turning a mid-tier city into a semiconductor and EV hub in under a decade.

Your point about building vs. regulating gets to the heart of why this approach is so transformative. Really appreciate you framing it this way excellent piece.

P.S Hefei was my City 1 of 707 cities of China, am now in City 13. Each week I cover 1 City. The pattern is the same even in completely different areas of focus. Its not just in Tech.